|

Boy, the Dog

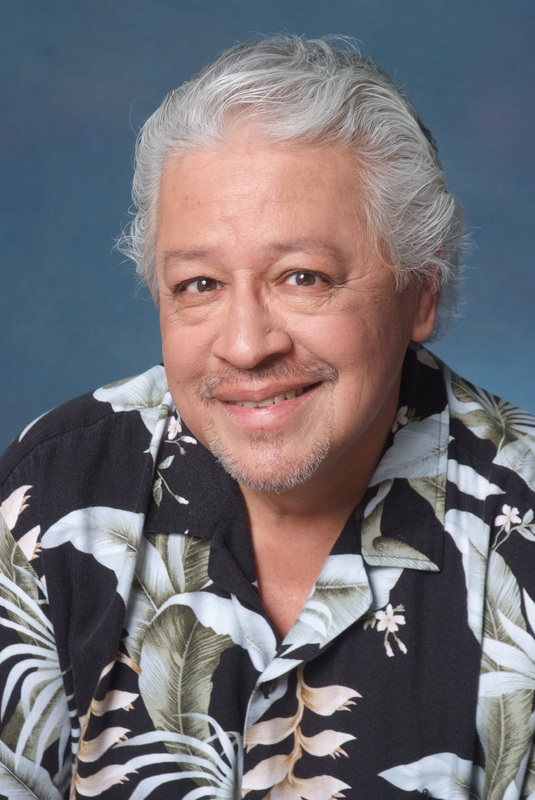

By Dan Ramirez Boy was the neighborhood dog. He was terrier sized, with a terrier temperament- smart, energetic, feisty. He was black and white, of indeterminate ownership. My Mother said he belonged to the Ortegas, my father said the DeCicis. I thought he belonged to the Greenwoods, who recently moved to Temple City. Mike Munoz told me his family thought Boy belonged to us. He was friendly with everyone in the neighborhood except the newest addition, the Mullers, who threw rocks at him or chased him with a broom if he came around their house. The Mullers had arrived from Cincinnati with two cats, one of which promptly disappeared. As Boy was a known cat killer, he was blamed for the loss of the precious Precious. I personally thought that any cat named Precious did not belong outside and probably got run out of the neighborhood by the other cats as an embarrassment to catdom. Boy would come to the back door to visit my mother, barking his greetings-- and begging for scraps. "You have a visitor," I would tell her, sitting at the kitchen table doing my homework. "I know, I know," she would say excitedly. "He knows I have something for him." She digs through our packed fridge, Boy's barking becoming more insistent. "Hold on, hold on. I've got some yummies for you." Gristle, steak bones, old spaghetti, menudo scraps-- gulping, grinding, gnawing, Boy gratefully made it all disappear. Boy and my Mother would sit on the back stairs together after he ate, Boy letting Mom hunt for fleas in the white fur around his neck, popping them between her nails while whispering, first scolding him for having fleas then providing tips on how to avoid getting pulgas. Sometimes she would softly sing to him. Boy would sit very still, ears attentive to her words, panting quietly, tail slowly wagging. They were friends. Soon after Boy becomes a regular at the back door, my mother sets out water and an oval rag rug on our front porch. A couple nights a week we heard Boy climb the stairs and cross the porch, his nail clicking on the smooth cement. A noisy, slurpy drink, a small thud as he settled, and Boy was in for the night. Mom always kept the water can full and the old rug neat and shaken. Late summer afternoon. I was sitting at the kitchen table eating a PB&J sandwich after a hard day at the public pool. My mother was puttering in the kitchen. "I almost hit Mrs. Muller today," I mumbled around sandwich bites. My mother stopped. "What? "I said, I almost ran into her. Her car. On my bike. Me and Boy were on our way home when Mrs. Muller came shooting down her driveway in her big blue Chrysler." "Don't ride so fast." "I was tired and it was hot. I wasn't going very fast." Pause for a bite. "I don't think she saw us. She just went rolling down the driveway and into the street." "Us? Who were you with?" "Boy. I just told you." "Did she say anything?" I just told you. She didn't see us." "OK. Well, be careful. Mrs. Muller's new here and is still getting used to the neighborhood." That night, she told my Father about the Mrs. Muller incident. "She's a terrible driver," he said. "She just learned to drive when they moved here from Cincinnati. She's still not very good at it. And that boat she drives.... Tell him to be more careful around their house and driveway. Especially when he's on his bike." It was early Saturday morning and I had just said a drowsy good bye to my father. He was going into work for a half day of overtime. Now he was back in the house, speaking to my mother in a low voice. "Get an old blanket. Quick. I don't want the kids to see." "What?" She asked. "Bring it outside," he replied, closing the front door. I rolled out of bed and looked out the front window. My father was standing at the end of our driveway. Something black and white was at his feet. I looked closer. My mother came down the driveway, holding an old bedcover. She stopped and her hand went to her mouth. We realized at the same time that the black and white lump was Boy, and he wasn't moving. My father took the bedcover and wrapped Boy in it, carrying him to our backyard. Mom stood in the driveway for a bit, hands occasionally wiping her eyes. She came into the house and made a phone call to my father's work, telling them that he would be a little late. She listened for a moment, then said good bye and hung up. I put on my slippers and met her in the kitchen. Her eyes were red. "Boy's dead." "Mrs. Muller killed him." She looked startled. "Why do you say that?" "Well, she didn't like him, thought he killed Precious and Dad said she's a terrible driver." "Don't say that. Maybe he got killed crossing the street." I shook my head. "No. Mrs. Muller did it." I went out the kitchen door to our backyard. My father stood in the middle of our yard, Boys' covered body sitting at his feet. "Boy's dead," he said. "Mrs. Muller did it." He looked at me. "I want to bury him. Here. In our yard." I point to the big lemon tree in the yard. "He used to like to snooze under the lemon tree during the day." I smiled. "Sometimes he would snap at the bees that were around the tree. I told him to watch it, not to get stung, but he still did it. I guess the bees bugged him." I pointed to the house. "And Mom can see him from the kitchen window. Wave hi, you know." He nodded his head. "Ok. Get the shovel." We dug a hole for Boy. Into the hole with his wrapped body I added his water can so he wouldn't get thirsty. We covered him with dirt, topped with heavy rocks so no animals could dig him up. Mom didn't join us, but I think she watched from the kitchen window. My father kept it simple. "He was a happy dog." Back in the house, Dad cleaned up, gave Mom a long hug and went off to work. I also gave her a long hug. "He was a happy dog," I told her. I was riding home from the park a couple days later, when Mrs. Muller came bombing down our street in her big blue Chrysler, too fast, not seeing me, eyes rigid on the road, strangling the steering wheel. The right headlight was smashed. © Dan Ramirez Dragged In Cat By Dan Ramirez I found the black cat one morning, thrown on the front steps like a dirty gray rag. I thought he was dead, until I noted breathing and saw a green eye studying me. I bent to examine him. He hissed a warning, but had no strength to actively resist. Some thousand dollar weeks later, at the guilt-induced urging of the vet, I reclaimed him. Clean, free of parasites, re-hydrated, infection free, (some combination of infected cuts from fighting and bacterial cat fever had brought him to my door,) and newly neutered, he still did not present the picture of grand health. Gaunt, he moved slow, with a limp, missing jumps and had a miserable meow. If a cat's purr is akin to the sound of a well tuned V8, his purr skipped on a few cylinders. When we got home I placed him on my porch where I had found him weeks before. I expected him to wander off from where he came, with a minimum of thanks. The next morning I opened the door and found him curled up on the welcome mat. He gave me a feeble meow, creakily stretched and slowly limped into the house. He paused at the kitchen door, looking at me expectantly. He meowed. "What?" I asked him. Another meow. "What?" A weak, just audible meow. Oh. I cooked us a concoction of eggs, shredded chicken and cheese. He ate heartily , drank water from a coffee cup I put out, cleaned himself. I followed him as he explored the house. The corner of my bed was flooded with sunlight. After he failed twice, he let me lift him onto the bed. He felt bony and didn't weigh very much. He positioned himself in the sun. A little more cleaning, the black cat slept. I checked on him through the day. The sunlight moved. He slept. Turned on his back, feet in the air, he softly wheezes. Late in the afternoon, working at my desk, something furry glides across my calves. I check and see two big green eyes looking up at me. A small meow as he ambled toward the kitchen. I've been adopted. Or hired. © Dan Ramirez ***As a young man, Dan ignored the voice of his writing Muse, plunging into the work force, working to be “a success”. His intermittent writing "career" was littered with journals filled with more empty pages than words. Years passed. Life changed. Business success, a supportive family and the Creative Writing Program at the local JC, Glendale Community College, allowed Dan to retrieve, like a dusty old manuscript, his writing career. Forty years after high school, he took his first creative writing class at GCC. This Fall, four years later, Dan will receive his Creative Writing Certificate from Glendale Community College, Glendale, AZ.

2 Comments

BOBBY JOE, MONTHS LATER

By James E Cherry Three years later, I browse the shelves of the downtown library in the shadows of late afternoon where Bobby Joe materializes among jazz cd’s, new book releases and the New York Times. He has stumbled through its public doors dishelved, burdened with bags under arm as if he were a scale and life had found him wanting, dreams with holes punched in them. We slap hands, take the edge off awkwardness with idle talk, before I tell him that I’d hope to see him again, that I’d written a book, Loose Change, that one of the poems was about him. He shrugs, turns down the corners of his mouth, rubs his chin, remarks: that poetry is some deep stuff and that he wanted me to take a look at something. We seize a corner table near the periodicals where Bobby Joe pulls a small black and red book from his bag. I finger the book, peruse a few pages, flip back to the front cover: Zen Meditation Book. I tell him that this is in the same family as poetry, may even be a first cousin, just another way of being in the world. I give the book back, but Bobby Joe tells me he has no need for it anymore, that he could live it, if he wanted to. I promise to carry a copy of Loose Change in the trunk of my car for the next time. Bobby Joe pushes himself up, gathers his bags, nods: next time and heads for the new releases where he stands before a wall of books until he becomes one of them. DREAM OF MY FATHER By James E Cherry My father looks the same as the day he died. Such is the nature of dreams. Actually, he looks like the man who dragged eight hour shifts of union dues and assembly lines through the front door at day’s end, frowned at the daily paper, grunted the six o’clock news, whispered grace over supper around a square dinner table. I’m at the head of the table this time. He sits to my left works a plate of cabbage and potatoes, wears the same mask the day I quit the high school basketball team in mid-season, was caught smoking pot in the basement, broke the promise of a college diploma into several pieces. I offer him the roast beef on my plate, but he says nothing, moves away from the table and when I rise to run after him, daybreak catches me around the ankle leaves me sprawled beside the bed to count drops of sunlight spilling from my eyes. THE SEGREGATED WORD By James E Cherry My sister calls from Nashville, asks where is she in my latest collection of poems, Loose Change her voice cloudy as a winter afternoon in 1968 where we climb steps to the public library, enter into its sacred space, follow the memory of our feet to the “Colored” section. I pet Clifford the Big Red Dog, look for my mom from the top of Jack’s Beanstalk, pat my tummy for a house of chocolate cake instead of a gingerbread one. I watch my sister and others, their Black faces bowing at the altar of study, fidget away from them into a land peopled by more books where a white lady with a sharp nose and round glasses rules over them. “Get back over there. Nigger.” Her words welt across my face, take aim at the other cheek before my hand is in my big sister’s and we’re back behind the safety of color lines. She rearranges me in my seat, strides across the aisle where her words grab handfuls of the white woman’s hair, their voices crescendo of curse and epithet. She reappears with a smile and an armful of books, instructs me to “read these” as I open bound leather, where a solitary tear staggers from my eye onto the red nose of a reindeer, its glow neon against the night, my hands grasping for stars and the moon around Rudolph’s neck, my life, strapped upon the back of the wind. © James E Cherry *** James E Cherry is the author of five books: a collection of short fiction, a novel and three volumes of poetry. His latest collection of poetry, Loose Change, was published in 2013 by Stephen F. Austin State University Press. His prose and poetry has been featured in numerous journals and anthologies both in the U.S. as well as in England, France, China, Canada and Nigeria. He has been nominated for an NAACP Image Award, a Lillian Smith Book Award and was a finalist for the Next Generation Indie Book Award for Fiction. Cherry has an MFA in creative writing from the University of Texas at El Paso. His novel, Edge of the Wind, is forthcoming in October 2016 from Stephen F Austin University Press. He lives in Tennessee. Visit: http://www.jamesecherry.com. |

Kimberly WilliamsKimberly has been fortunate to travel to half the Spanish-speaking countries in the world by the time she was forty. As a traveler into different cultures, she has learned to listen ask questions, and seek points of connections. This page is meant to offer different points of connections between writers, words, ideas, languages, and imaginations. Thank you for visiting. Archives

October 2020

|

- Mission

- Visión

-

Literatura

- Saúl Holguín Cuevas

- Armando Alanís

- Josué Alfonso

- María Dolores Bolívar

- Oscar Cordero

- Esteban Domínguez

- Juan Felipe Herrera >

- Miguel Ángel Avilés

- Escritor/a Invitado/a

- María Candelaria Cuevas

- Magali A. Solorza

- Héctor Vargas

- Miguel Ángel Godínez Gutiérrez

- Entrevistas

- Diversidades infinites

- Lengua liquida

- Literatura 2

- ARTE

- MÚSICA

- Cine

- Galería de fotos

- Enlaces / Links

RSS Feed

RSS Feed