|

Because the Dead

I was late for the funeral. The cathedral tilted, and once I started walking under its arch, it grew and became like a city unto itself. People advanced through the large wooden doors, dressed in dark suits and skirts, traveling in pairs, like animals disembarking from Noah’s ark. I also wore grey (with black pumps), and I knew it wouldn’t matter that I was late for the funeral. Although I had never been here before, I knew I’d blown across the sea. (Maybe that’s why it took so long to get there. Maybe that’s why I was late.) I knew I had to arrive, but it didn’t matter that I was late. Only that I appear. I had the vantage point of an angel’s--peering down from the gargoyles. It didn’t matter that I was late for the funeral because it was mine. All of us attending, at some point, kneeling in the pews, genuflecting in the aisle, lying still in the casket. Jesus, Joseph, and Mary, it was like a litany of the saints: Harvey, Irma, Jose, Lidia, and then Maria slaughtered Juan. No one survived. It didn’t matter that I was late for the funeral because the dead are still filing through. *** Tri-Angles The guy with the red beard doesn’t believe in angels. He goes out of his way to announce this, inserts it into the writers’ group as casually as kneeling down to tie a shoe. But he knows I am the one who knows angels, I read my poems about them the night before the day of his proclamation. He must be thinking of them literally (the angels not the writers). He must think that I think of them flying in white robes and halos. He doesn’t think about the angels formed from ashes and acid, rancid trash and smack. The guy with the red beard writes about drug culture and doesn’t believe in angels as if no user ever hallucinated before. The guy with the red beard has a voice that sounds like a tricycle wheels careening across cracks in the cement—as when a child circles his three wheels over and over the same fractures in the same O, like he’s riding around a cracked circus ring, and the red beard’s cement voice thuds over syllables like VERy and VEdas. This red-bearded guy doesn’t believe in angels, but he’s interested in depicting the ‘dark side of life’– you know, drug culture, and such, because no angel ever drifts around low-down addiction – angels only dance on clouds swathed in glorious beams of light. © Kimberly Williams

0 Comments

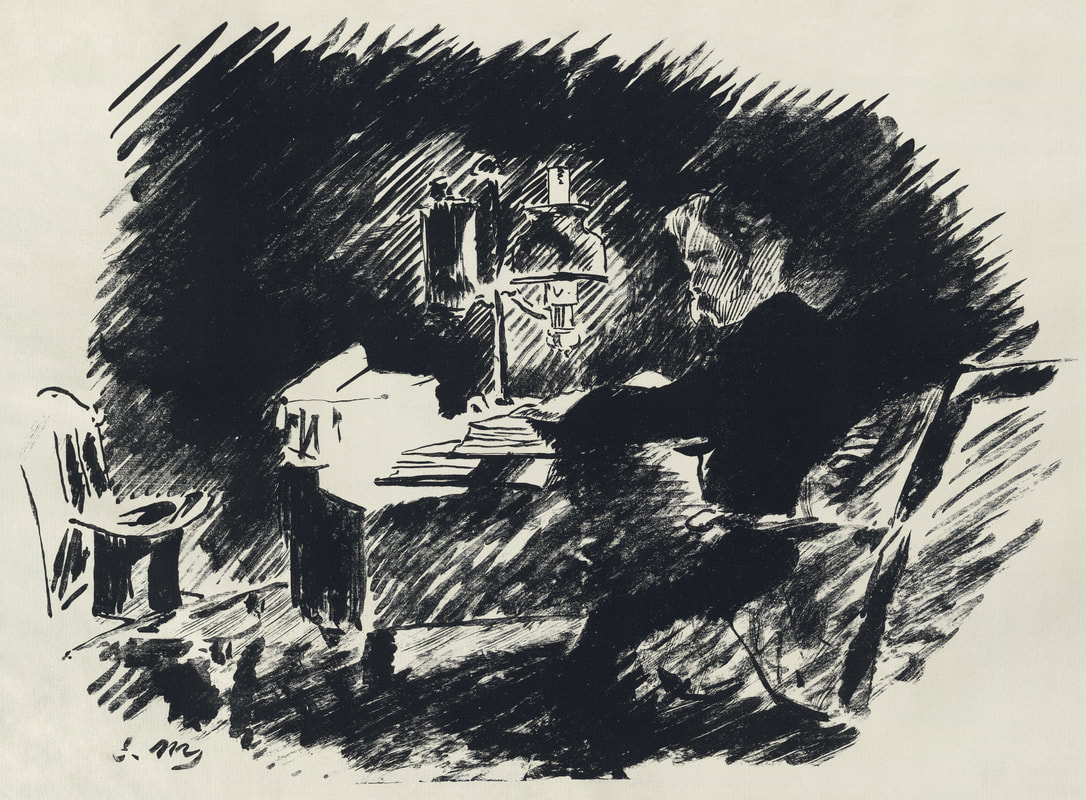

The Man Who Almost Wrote a Poem In his youth, he worked first on the title. He wrote it out longhand on yellow tablet paper: The Poem. He looked at it, crossed it out. He tried “13” as a title. But he wasn’t sure if 13 was technically a number? a word? He spent months on the title: Trapped at Night in The Mercado. The Hungry Dog Chases Me and I Am Paralyzed. No seas pendejo. Losing My Teeth to Lisa. Ode to 43. La casa anaranjada. El hijo de su reputa madre. In his dreams, he saw titles floating in front of him, But they disappeared once he woke, evanescent slipping away, much like the years. He wrote down what he remembered and stuffed the title pages away in his desk drawer. For later, he thought. The titles thus drawered, He turned to the poem. One week he wrote twenty-nine, page-long stanzas of his poem, Each stanza 175 words. He did not sleep. He missed work. He put it all away in his desk drawer, for later revision. In his twenties and into his thirties, he had writer’s block for ten years. He would sit at his desk for hours on end, staring at the blank page, the pen, his hand. He tore the cuticles from his fingers until his fingers bled. He would dab the blood from his fingers with Kleeenex and save the Kleenex in that same drawer. He couldn’t write, but he thought that suffering was good. The Kleenex reminded him and would help him write poetry, perhaps later, when the block lifted. He suffered much, he thought. Good, he thought. Maybe next decade, he thought. Sometimes he wrote in English. Sometimes in Spanish. He would mix the two languages Just like they were mixed in his head, in his limbs, in his mouth and eyes and tongue and brain and in the tattoos he thought he would get but never did. At work, over the course of thirty years, as he sat next to Bob and Vanessa and then others from accounting, he looked over his shoulder and wrote a few lines every day. Bob and Vanessa looked at him, then each other, and rolled their eyes. He could see them roll their eyes, and he sometimes wondered if they had stronger eye muscles than he did. His eyesight was dimming. When it was time to go home, he put the lines in his briefcase and scurried stealthily past the security guard, hoping no one would look in his briefcase. No one ever did. Once home, he emptied his briefcase into his desk drawer. Before bed, he went to the bathroom mirror, looked at his eyes, and did some eye rolls to strengthen his eye muscles. He practiced his eye rolls with his wife, but she did not understand. He slept on the living room couch. One other night, back in his bedroom, he angered his wife when, in the middle of a heated argument, he picked up a pen and a used Kleenex. I have an idea for a poem called The Argument he told her. He wrote what he could on the Kleenex Before she tore the Kleenex from his hand and threw it at him, the Kleenex fluttering like a bird he had seen flysmack into their bedroom window one sunny day, and, much like the bird, it fell and splayed silently at his feet. Eres un pendejo she spat at him as he bent over to pick up the dead Kleenex. He went to his desk, and wrote down Eres un pendejo and Dead Bird. He could hear his wife crying in the bedroom. He stuffed the shredded Kleenex into the drawer. He went to comfort him, but she said ¡No me toques! and closed their bedroom door. He could not help but think “Don’t Touch Me!” could be the title of a poem. He often woke up at night and wrote a word or a line or a reminder on scraps of paper, and they filled his nightstand drawer. One day his wife threw the scraps of paper in the trash. “No!” he screamed to her as he looked at her in horror. He rolled his eyes. She left him then. She left him a goodbye note on a Kleenex, “Hijo de tu reputa madre, you are a big and sorry pendejo.” “Ah, poetic justice,” he thought. He kept the note. Over the course of time he forgot and lost more of the poem than he ever wrote down. He would have dreams that were poems, but as soon as he woke he would forget. He had only the vague feeling of having dreamed the faces and bodies and outstretched arms and eyes and mouths of loved ones. Though the feeling was vague and became vaguer and then lost completely, he thought it was a good feeling. He could not write words to capture what was gone, so he drew pictures to try to capture the dream. He drew red and yellow waves, a half-eaten ear, uneven teeth, a house that leaned almost to the ground, a pinstriped yellow and black jaguar with purple horns, And a tree with leaves from which hung old contortioned blue station wagons that made the branches of the tree bend down to the ground. There was always some interruption, the phone ringing, someone at the door, girlfriends, love, breakups, wives, daughters, work, travel aging parents, friends who entered his life, many of whom left, though some stayed. He would show those who stayed his unfinished poem. They said they liked it. In his mind he saw them rolling their eyes. Dissatisfied, he would stuff the poems in his drawer. One year, he wrote seventeen syllables-- first five, then seven, then five again-- all of it centered on the image of a duck that had lost a wing but could still fly, though in small and tight circles that overlapped, just enough so that the duck covered some small distances but always veered to the left. It would alight, whether in water or on dry land, and it would walk around in circles, dizzy, and it would vomit worms and small partially digested fish and grass. Dizzy Duck he called the poem. He was happy with the poem and thought the title was genius. Someone praised him, said what a wonderful haiku. Pinche madre he said in anger. He did not want a haiku and balled it up and threw it into the drawer. And so it went for the span of his life, which was long and good in some ways, but relatively unremarkable. There were the births and deaths, marriages and divorces, and moments when life seemed crystalline, children going to school, growing up, moving out. Where did they go? There were moments when he didn’t know how people continued to live in the midst of such pain and misery and suffering and horror-- The husband who came home to find his wife, sitting in a chair in the hallway entryway, half her head gone to the shotgun blast, their two boys shot in their beds, blood-soaked pilllows. But these moments passed. He focused on his poetry. One night, late in his life, he went to his desk. He pulled hard on the drawer and looked at it jammed full of papers, bits and pieces of Kleenex (some with dried blood), loose typed sheets, notebooks and journals, some full of writing, many blank, some with numbers, drawings that seemed as if drawn and colored by a child of two--of trees and allegorical animals and cars that flew among oddly shaped clouds, one cloud looking like the prosthetic leg of Santa Anna, or so he thought. There were balled up bits of scraps of paper and napkins, some receipts. Memory cards. Floppy disks. Thumb drives. Passwords. He looked at the contents of the desk drawer with confusion and concentration, the same way he looked when he walked into a room and forgot why he had walked into the room or when he opened the refrigerator and stared inside and then closed the door, having gotten nothing. But this time, when he walked away, he did not suddenly remember that he was looking for his glasses, or orange juice. He sighed and struggled and closed the drawer shut and shuffled to his bedroom. That night he could not sleep. As he lay in bed, he thought of his poem. He was close to something he thought. He felt a faint smile cross his face, his eyes widened and glistened as he finally came upon the way to write the poem. He turned to tell his wife, but she was not there. She had been gone a long time. He wrote himself a note. He would have written Eureka but felt that there must be a better word. Instead he drew a picture of a balloon, a number, some other figure and fell asleep and slept the sleep of a younger man. He dreamed of old girlfriends, of being young, of the first car he ever had, driving it fast in row after row of a junked cars. He dreamed of the first girl he loved. The girl he always loved. He dreamed of living in another country, the sound of the ocean, the smell of mango, the taste of a peso as he pressed his tongue to it, a dog he had, its bark almost waking him. In his dream, his daughters appeared to him and called him “papi,” and they spoke Spanish to him. He dreamed of old friends and in that half-dream state he knew that some of those friends had long been dead. He moaned in his sleep though no one heard him. He dreamed his parents, long ago dead also. In his dream they were young. They called to him, “mi hijo.” The next morning, One of his daughters came to the house to wake him, “Papi,” she said as she walked into the bedroom. He did not respond. She cried as she sat next to his body on the bed and held his cold hand. She looked over and saw the scrap piece of paper on the nightstand, the number 13 scrawled on it. A yellow balloon. A happy face. © Jaime Herrera Jaime H. Herrera is currently a Professor of English at Mesa Community College. Jaime is a product of the Juárez/El Paso border, a place he holds dear and which embodies who he is, as much Mexican as American, as much Mexicano (and mexinaco) as he is estadounidense (and gringo). He is bicultural and bilingual (and speaks a good Spanglish too). He knows that the border is a space that cannot be fenced. La frontera es un espacio que no se puede cercar. He loves translation, the back and forth between the two languages. Also. he writes his own poetry in both English and Spanish and has written a novel (as of yet unpublished), tentatively titled This is not Juárez. When he dies, he wants his ashes spread right in the middle of the bridge that connects Juárez and El Paso, his ashes blowing in both directions.

|

Kimberly WilliamsKimberly has been fortunate to travel to half the Spanish-speaking countries in the world by the time she was forty. As a traveler into different cultures, she has learned to listen ask questions, and seek points of connections. This page is meant to offer different points of connections between writers, words, ideas, languages, and imaginations. Thank you for visiting. Archives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed