|

Por Kimberly Willams

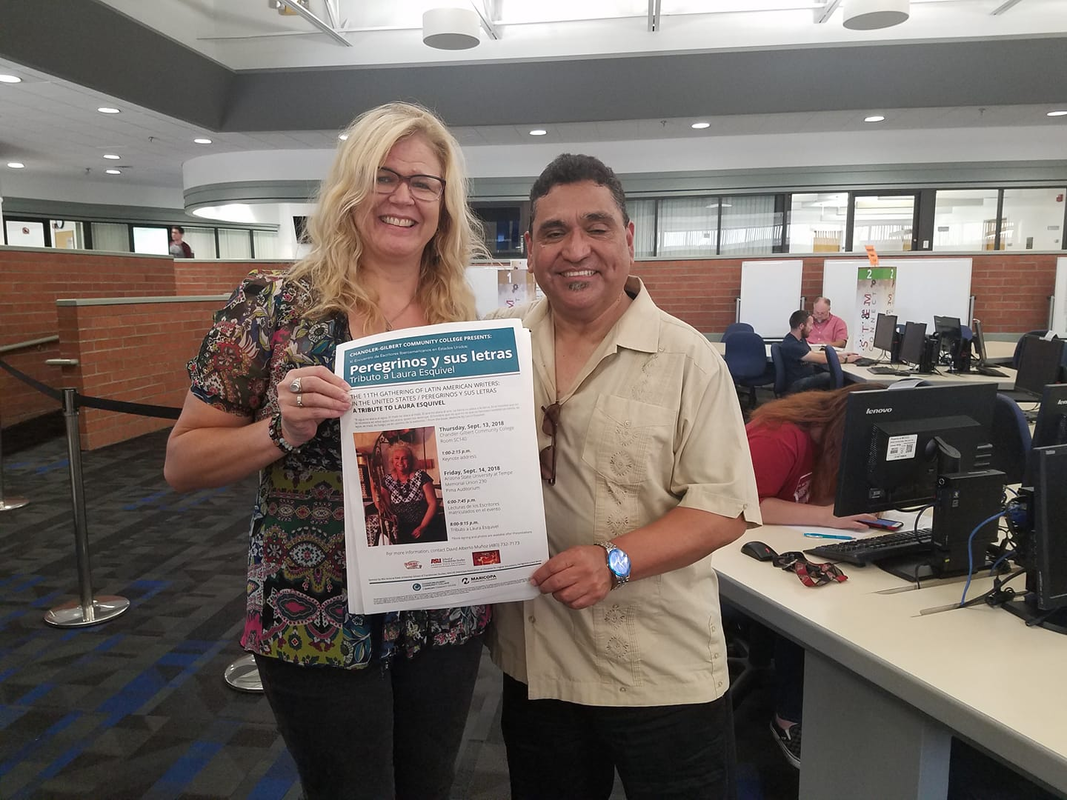

for David Muñoz (1959-2020) My friend, when I realize you are gone, have passed, I panic. I am a house sparrow caught in a jar with the lid fastened. Your spirit stretched wider than death. I couldn’t fathom that you’d ever really go. The zócalo in San Miguel de Allende couldn’t contain you or your song the night you joined the trovadores roving the plaza, and I recorded the spontaneous joy on your phone. We walked up and down the hills of Guanajuato together, despite your need for new knees, and when I made my late-night visit to the panadería for conchas, you waited outside with the scent of baking bread for company. Words stayed away for months after you departed, did not appea for weeks, and still a part of me does not believe because your spirit keeps lengthening --wider than the pyramids we walked among at Teotihuacán. When I think of you gone, my heart is a trapped sparrow, wings swiping the glass, beady eye glancing beyond. Ademas, here is a photo of us. I wish he weren't blinking in it. But anyone who knows David knows that he mostly took the photos, and so they are gone with him as I don't see his family (I live in Australia now). and I only have a couple of us. This one is best for this purpose, I think, because it was in collaboration for Peregrinos. Gracias por todo, Kimberly

0 Comments

María

A short story by Jaime Herrera María and I sit on my bed playing Barbies. As the afternoon storm gathers, we hear my brother riding his bicycle outside on the sidewalk. We look at each other. She makes a face as if she is eating a lime and I laugh. My brother, who is three years older but was born on my same day, the 10th, never plays with me. He says he cannot play with me because I am a niña and he makes the same sucking lime face when he says “niña,” as if his teeth hurt. It has started lightning outside and my grandmother screams “¡María! Los espejos.” María says she’ll be back later. She has to cover all the mirrors with sheets because of the lightning. When it starts raining, mother screams at my brother to come inside. He comes in, rolling his eyes, mouth twisted in a scowl, sits cross legged on the floor of the room we share. I ask him if he wants to play Barbies with me. “No. Eres una niña.” I show him the new Ken doll that I got on January 6 for Día de los reyes magos and the pink car that came with Ken. “No. Eres una niña.” Later in the day he looks out the window at the steady rain and without looking at me says, “Just this once and don’t tell anyone.” We play that Ken and Barbie are married and have two children, a boy and a girl, and Ken drives his car across the border to work every day and says “American” at the border in order to cross into the United States where he works. He comes home at the end of the day and Barbie makes red enchiladas and refried beans for dinner. Sometimes Ken comes home very late on Fridays and has been drinking tequila and sometimes the car has a dent in it like it has crashed and Barbie’s makeup runs because she cries late into the night. The children wake up as the sun is almost rising and go listen to the mariachis in Barbie and Ken’s bedroom and when the mariachis sing “María Bonita” Barbie stops crying and the music makes their love good again. They are all crowded in the bed and mother Barbie takes father Ken’s cowboy boots off because he is flopped snoring on the bed with his boots still on. As my brother and I play I hear the front screen door open and shut and my cousin Toño comes running into the house wet like a dog. I hear my grandmother screaming “¡María!” to get the mop. When my brother hears my cousin, he stops pushing Ken’s car across the floor and grabs hold of my Barbie and makes Ken hit Barbie, making noises like “Bam!” and “Pow!” just like on the Batman television show we watch Saturday mornings. Just then Toño comes in the room and looks at my brother first and then at the dolls, his eyes wide, eyebrows arched. My brother tells him Ken is beating up on Barbie because she cries and my brother laughs and his laughter hangs in the air. All I hear in my head is the rain steady outside, and the drip drip of rain on the pots and pans in the house where water leaks. Then my cousin laughs too. I start to cry and then my brother calls me a niña and he and Toño leave and I am alone with my stupid dolls. I am crying, snot running down my nose, and then María comes into my room out of nowhere and tells me not to cry. “No llores,” she says. She tells me that boys are “pinches pendejos.” She hugs me and I smell the heat and the dust from her. I stop crying. I feel better and she leaves to do her work. As the rain lessens, I go and sit in our small, warm kitchen, awash in the light reflected off the neon yellow walls, smell of pinto beans cooking as they gurgle on the stove in my grandmother’s old earthen pot. I stare at our Jesús clock on the wall. The downcast eyes of Jesús stare back at me from underneath his bloody crown. I look away. I am not good at telling time. Even so, the crucified Jesús face kitchen clock my grandmother bought at the mercado is broken, and even when it worked, I had trouble telling if the time was for us in Juárez or for my father working across the border. Border people say “tiempo de Juárez” or “tiempo de El Paso” to clarify. But it does not clarify for me. Plus, Jesús’ sad face bloodied from the crown of thorns staring back at me scares me. As if he is judging me for not being able to tell time. I play the staring game with him sometimes, but I always look away. Jesús always wins. I sit and listen as the beans cook, the clock ticks. I have not heard my father’s car, him parking it out on the street under the old and dying sycamore tree on the side of the house, him whistling as he walks into the house and calling “¡Ya llegué!” as he goes into the kitchen. But it’s Friday and on Fridays he comes home late. “Viernes Santo” he says the next day and laughs. I laugh too but I don’t really know why I laugh. And even though I can’t tell time, it is late and I know night is coming. I like the night and I know it is getting night by the way the shadows from the house across the street get longer on the street outside when I look out the kitchen window. I get up and walk to my bedroom. I hear Maria’s chanclas on the cement floor as she nears my bedroom and then she asks “¿Se puede?” and I say “Sí” and she opens the sheet we use as a curtain that leads into the bedroom I share with my brother. She peeks in and says “Hola Niña” and then comes into my room. She and I sit on my bed and play with my Barbie dolls. I smile at her and she smiles back, her teeth white against her dark skin. María has been with us for two years. She knows how to sew and iron and she made a dress for my Barbie with one of her old dresses that she no longer used because we gave her some of my old clothes. My grandmother tells her to use her dress for rags, that her old clothes are only good for rags. “Trapos,” she says and María looks down at the floor when she hears that word. She is older than me but not by much, yet she knows how to count to one hundred and she knows all the letters of the alphabet though my mother tells me she stopped going to school in fourth grade to work for us. I do not understand why she cannot go to school and why she has to work. I wonder about María’s mother and if she lets her work and I ask my mother one day “¿Y su mamá?” and my mother says “Está muerta.” That’s when she came to work at our house. “Está muerta” rattles in my head. The day after mamá tells me this I find María washing in the back room, standing on a little wooden stool so she can reach over the sink. I walk up to her and hug her and she asks “¿Estás bien?” as if something is wrong with me but I say I am fine and that I am sorry about her mother. Her eyes water and she brushes the tears back with her hands full of suds and she hugs me tight and says “Gracias Niña.” I can smell her. My grandmother tells her she needs to take a bath and when she says this María looks down at the floor as if she is looking for a safety pin and she does not say anything. María smells of burnt corn tortillas, the heat of the iron, sweat, and broom dust. I don’t mind how she smells though. She smells of María. I know her smell. Almost every day, as soon as she is done sweeping and mopping and sewing and ironing clothes, she plays with me. Tonight we play Barbies on my bed and wait. At night all the comadres in the neighborhood bring out their little wooden stools and sit outside. The coolness of the night calls to them and they walk out from their hot houses, all the women drying their hands on their aprons as they walk out. They say “Buenas noches” to each other and sit on the sidewalk outside our door, the bare bulb outside our house giving off a wan light. My mother and grandmother join them. Señora Herrera is the best cook and tells them how she makes her flour tortillas. The ladies listen. Señora Balderrama always has some neighborhood gossip to share and the other ladies ooh and ahh as she tells them about what really goes on in Doña Elvira’s house after dark. María and I listen through my window and vow never to go to Señora Elvira’s house again. That’s when I ask my mother through my bedroom window, “¿Puedo salir a jugar?” and wait to see if she will let me go outside and play. I can see my cousin Mayela out my bedroom window as I stand on my bed on my tiptoes. When she sees me, Mayela motions to me to come out and play and she mouths the words “Ven a jugar.” María stands next to me on my bed. She jumps up and down a little bit on my bed and covers her mouth with her hands. We wait. Then my grandmother asks María through the window if she has finished her work and she says “Sí señora” and I see my grandmother nods at my mother and my mother says we can come out to play, “Salgan.” I look at María and she is smiling big and she hugs me and I let out a little squeal of excitement and run outside and look back as María walks outside and says a proper “Buenas noches señoras” to all of the comadres and then as soon as she rounds the corner of my house she sprints after me, the sound of her chanclas bouncing off the street and off the walls in the dark of the night. We play tag and hide and seek with my cousin and her new friend Angelina who has just moved into the neighborhood and with the two sisters who live up the block. They are twins and I never know their names and we all just call them “Las Cuatas,” as if they are one and the same and always together, and they are, though one is skinnier than the other and so we call one Cuata Gorda and the other Cuata Flaca. When we play tag I always hide behind the sycamore tree but María comes and grabs me by the hand and whispers “Ven” and we hold hands as we run and hide behind the garage door of our neighbor, in a cranny just big enough for the two of us. We hold hands and are quiet and I can feel our hearts beating to the point of wanting to scream but María whispers to me to be quiet and I listen to her. The other girls never find us there and we win. We play mamaleche we have drawn in chalk on the sidewalk, María always the first to hop from 1 to 10 and win. We play la tiendita and trade bits of yarn and jacks and old playing cards and soda pop caps. Time seems eternal, but I know it is getting late when I hear the comadres saying “Buenas noches.” I glance at them and they are picking up their little stools. I know what is coming even though I try not to hear and sure enough my mother says “Paulina. ¡Ya!” I look at my cousin and her friend and at Las Cuatas and shrug my shoulders and say to María that we have to go inside. “Adentro,” I say as if it is the end of time. When we go inside my grandmother tells María to make me dinner. She stands on her toes to reach the stove and warms up beans and tortillas. I look at her and ask her if the fire burns her fingers when she turns the tortillas with her hand but she says no and that she is used to it. I tell María I wish I could be like her and she says I am silly and not to wish such things. She and I eat sloppily and I get full fast and do not finish my beans but María uses her tortilla to clean the plate so clean I think she does not have to wash it, but she does have to wash it. My grandmother makes sure. María tells me in a whisper how sometimes she just washes the dirty side of the plate, and not the back and somehow that makes me laugh so hard I almost fall off the kitchen bench, my arms flailing backwards until María catches me. She wipes her eyes with her apron she is laughing so hard also. When we are done eating, my grandmother tells María to help me get ready for bed and I get my pajamas and brush my teeth and offer María my toothbrush to use because she says she uses her finger and just water but my mother hears me from her bedroom and says “¡No!” Then my mother comes into my room and kisses me goodnight and calls me “angelito” and makes me say my angel de la guarda prayer so nothing happens to me at night. I teach María the part of the prayer I know because she says she does not know it and her mother is not there to teach her. I teach her. “Ángel de la Guarda, dulce compañía, no me desampares ni de noche ni de día.” And I tell her that the prayer will keep her safe all day and all night. When I say this, she is very quiet and I ask her if anything is wrong and she says no and she is crying and I hug her and she stops crying when my mother comes into the room. My mother takes out some peso coins from her little plastic change purse and gives them to María and says she should hurry and go home. María gets her little bag with some clothes we gave her and day-old corn tortillas. She walks out the door and into the night. When she is outside, she comes by my window and calls quietly to me and I stand on my bed and see her outside my window. She thanks me for teaching her the prayer and says “Buenas noches” to me and I say “Buenas noches.” I see her as she crosses the street and waits at the corner for the van that takes her home. I see the van that has the sign on it with the name of her barrio, Colonia Azteca, as it pulls up and she gets in. I can see her in the van when the light turns on inside. There are other people in the van, men and women, all of them staring out the windows of the van. She waves to me as the van pulls away and I wave too and then the van light turns off and I cannot see her but I look at the van still as it drives off and then I can only see darkness. Mamá tells me to go to sleep and I go to bed and fall asleep. That night I dream that someone is chasing me. I don’t remember the details of the dream but I know someone is chasing me and I know I am afraid and I run very fast and when a man is about to catch me, I startle awake. I call María’s name in the dream and say “María” quietly when I wake. María does not come to our house on Saturday. Not on Sunday either. She never comes on those days. But she will come on Monday and I cannot wait to tell her about my dream. But on Monday when I ask at lunchtime, my grandmother tells me that María is not coming today either. I miss María all day and at night after dinner my father comes into my room and he sits me on the bed and strokes my hair and he says that María is not coming anymore. I don’t know why but I start to cry and he hugs me and says he is sorry and then I am confused. I do not know why he is sorry. I ask “¿Mañana?” He says “No, mijita.” He tells me that something happened to María on her way home Friday night as she was walking home after the van dropped her off in the dark, on the dirt road that led to her house. Someone in the van saw a car pull up next to her as some men got out of the car and took her. I ask my father where they took her and then he says she was found the next day in a ditch by the old mercado. “¿Está bien?” I ask. I can see his mouth moving and he must have said many words but the only words I hear are “Está muerta.” That night I cry so much my eyes cannot see. I get my Barbie doll and I bring her to bed with me and I rename her María and when my grandmother tells me I cannot sleep with the doll my father says it is okay and I hug María tight to me. I say my prayer as I hug María close to me, her smell still strong reminding me of her: “Ángel de la Guarda, dulce compañía, no me desampares ni de noche ni de día.” I can smell María and, in my mind, I can see her waving to me from the van and smiling at me, telling me over and over, “No llores Niña, no llores.” © Jaime Herrera Phoenix in April

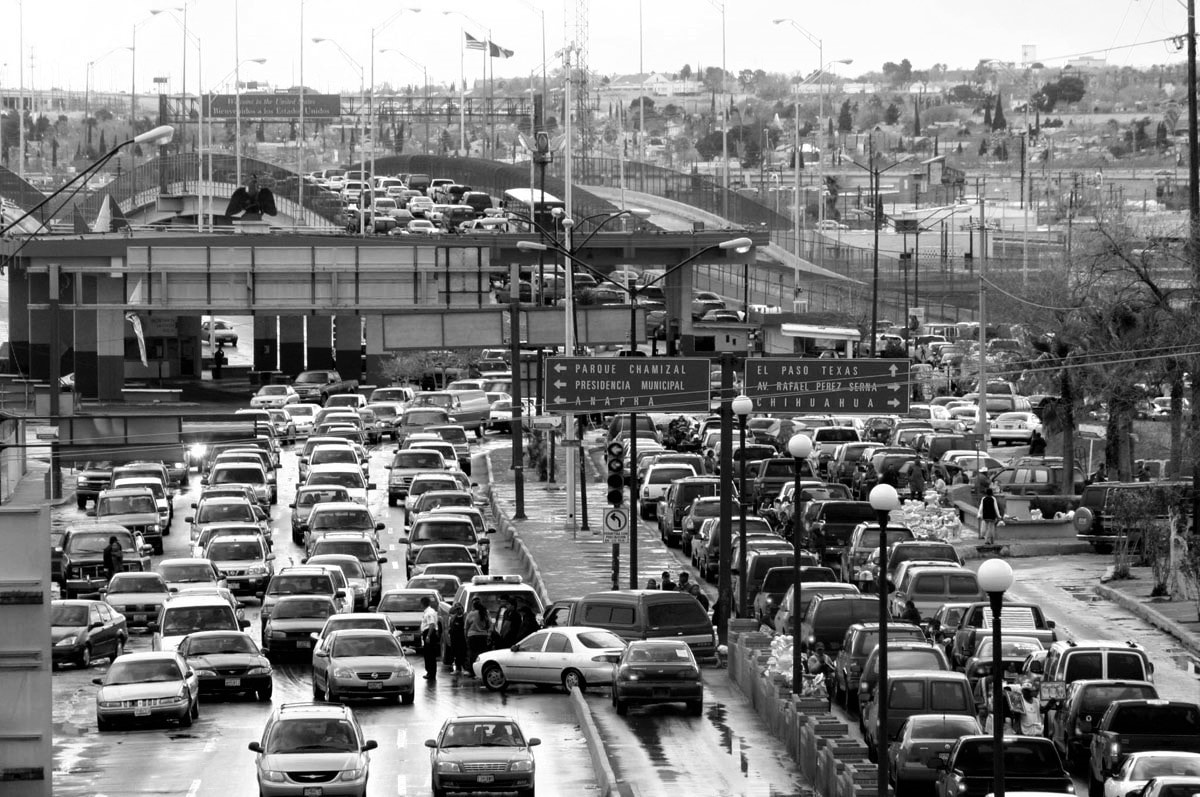

This could be any street in any city until we turn a corner and meet a flying buttress, thick and arched as a breaching whale. Over here, palo verdes in bloom offer yellow shelter to those who stroll beneath. Over there, David would follow the roundabout, cars pumping in and out like blood through the heart. I would scream at the oncoming autos--my fear his absolute delight. Over here, a campus waits, windowless slabs of geometric buildings, prepared for July’s heat. Over there, nothing prepares for such heat. Stone structures wider than whales cannot burn whispers one side: What has lived nine-hundred years cannot yield. On the other side, I have never been able to fully leave him there since he left me here. Sometimes, like a tiny voice aloft in a cavernous space, I still hear him say my name: Kimm-ee. Here and there, absence burns longer than fuel. Over there, we walked through the wooden doors, dipped our fingertips into the font: north, south, west, east. Our faith invisible until that moment. Over there, the spire is on fire while here the red yucca stretches crimson flowers—thin sparks shooting over green leaves. Here, I give the roundabout another go: a flash, a blink, a curve, a millennium furling into flames. © Kimberly Williams Inframundo (para Juaritos) Te adentras. Oscuro. Estás encajuelada. Ya muerta. O aun respiras. Y sonríes. O estás celebrando la quinceañera de tu carnalita. Bailas con tu jainita. Rola lenta. Tus compas echando birria. Las puras curadas. Tus papás y tíos contentos. Igual los vecinos. O entran hombres con botas vaqueras. Balazos. Te resbalas en la sangre, tu vestido manchado de rojo. Cuerpos. Gritos desalmados. O no tienes que comer. O comes buen refín de tortillas y frijoles refritos en casa. O en la calle comes burritos o tortas o caldos o chuletas o cocteles de camarón o menudo o pan dulce o hamburguesas. Hay de todo. O te echas unas cheves con unos camaradas (pero micheladas no, ya que están de acuerdo que las micheladas son una mamada). O no tomas licor. O andas por la 16. O tomas el camión Waterfil. O una rutera. O andas en tu wuila. O tienes tu ranflita con placas Front Chih. Y recuerdas la vez que ibas por la Juan Gabriel y la balacera estalló enseguida de ti y cayo el vatito muerto en la calle. Pudiste llegar a tu casa temblando y vomitaste del susto. O vas a la Juárez y bailas y oyes música y te pones tan pedo que no recuerdas lo que hiciste. O vas pedo en la Juárez y te roban y te matan y te dejan tirado en un callejón. O vas al mercado que se ha quemado infinitas veces, pero todavía está en pie (como la ciudad), y no compras nada más que los aguacates que te encargó tu jefita. O compras del vendedor un globito azul con blanco para tu niña de tres años. ¿Pero cómo si tú desapareciste al mes de haber nacido? O vas a la feria con la familia. Panzas llenas de elote en vaso y de mango con chile. Tu niña se gana un peluche Pokemón. Tu hijo se sube cuatro veces a los caballitos. Vas agarrado de la mano de tu pareja. O ese mismo sábado por la mañana eres uno de los 25 que mataron en el fin de semana. O la haces de periodiquero o de parquero y te dan tus propinas y así le das de comer a tus once hijos. O la haces de pordiosero. Te falta una pierna. Pero te vale madre. Duermes en la banqueta a la mitad del puente. Junto con otros. Son tu familia. O eres Tarahumara y pides Korima cerca del puente, tu bebita en tu rebozo. Tus huaraches se rifan el calor del pavimento. O trabajas en una maquila y abres tu restaurancito de mariscos. Y te va bien. O tu jefe en la maquila te acosa y le rayas la madre a él y a la frontera y te regresas a Veracruz. O te enamoras y te quedas. O bailas teibol. O vendes drogas. O las consumes. O lo haces todo porque no le tienes miedo a nada (más que a la nada). O andas de noche caminando por tu barrio polvoriento y saludas a las viejitas sentadas afuera de sus casas bajo el farolito poca luz. Buenas noches. O te saludan los viejitos de otra época sentados al fondo del restaurante jugando dominó. O llegas a la tercera edad y tienes a tu familia alrededor de ti. O estás sola. Y en tus sueños te acuerdas de la vez que hiciste el amor con Pancho Villa. O te violó. O vas a la prepa del parque con tu blusa blanca, tu falda con el patrón escocés, tus libros en tus brazos. Te gusta el muchacho en tu clase de química. O ya no vas a la escuela porque tienes que trabajar para ayudar ya que tu papá desapareció. O ya no vas a la escuela desde que encontraron la cabeza en el callejón al lado. O te fusilas al güey que te enseñaron en la foto y El Kartel te da quinientos varos. Y después te matan. Y ni te dura el gusto. O les dices que no vas a matar a nadie. Y aun así te matan. O te la pasas grifo con tus compitas y así perduras el polvo y el miedo y la desesperación. C/S. O te vuelves activista y buscas a desaparecidas. Aunque nunca las encuentras. Bueno, algunas sí, cuerpos en el desierto. O eres chavita fresa de familia bien y hay un tiroteo cerca tu casa. Tomas video con tu teléfono. Lo compartes en tu Face con un emoticono sonriente. Alguien hackea tu cuenta y te dicen pendeja, estás muerta. Tú y tu familia se van a vivir al otro lado. O aun siendo chavita fresa ya sabes lo que ves y te metes a tu casa. No viste nada. O vas en tu Mercedes en el bulevar y te sientes muy papi. Va caminando una muchacha con falda corta y le ofreces un aventón, a donde quieras chula. Se sube al carro y van a un motel de paso y se dan un buen agasajo y quedas de hablarle, aunque lo dudas ya que es una chola. O vas en tu Mercedes en el bulevar y te sientes muy papi. Va caminando una muchacha con falda corta y le ofreces un aventón, a donde quieras chula. De repente se para una camioneta 4x4 enfrente de ella. Se bajan dos guaruras, la levantan – ella grita y patalea – la meten al carro y se van. Un levantón. No puedes hacer nada más que sentir vergüenza y tristeza e impotencia. O ves en una barda de un edificio abandonado en el centro un mural que te hace llorar y llevas a tu novia después y el mural ya no está. Ni la barda. Ni el edificio. Pero tu novia te cree. Porque ve todas las posibilidades. Y por eso la amas. O de esquincle vas a una charreada con tu familia. Te gusta el paso de la muerte. O das tu paso de la muerte ya de adulto con una tranza que te deja un chingamadral de lana. O te encobijan y nunca nadie te vuelve a ver vivo. O te agarran en la movida y te mandan a la peni. Y aun estando adentro En lo oscuro Le echas ganas Como toda la pinche ciudad. Así es esta gente. Así es está pinche ciudad. Y por eso la amas. © Jaime Herrera ***Jaime H. Herrera is currently a Professor of English at Mesa Community College. Jaime is a product of the Juárez/El Paso border, a place he holds dear and which embodies who he is, as much Mexican as American, as much Mexicano (and mexinaco) as he is estadounidense (and gringo). He is bicultural and bilingual (and speaks a good Spanglish too). He knows that the border is a space that cannot be fenced. La frontera es un espacio que no se puede cercar. He loves translation, the back and forth between the two languages. Also. he writes his own poetry in both English and Spanish and has written a novel (as of yet unpublished), tentatively titled This is not Juárez. When he dies, he wants his ashes spread right in the middle of the bridge that connects Juárez and El Paso, his ashes blowing in both directions.

No hay manera (para mis padres) No hay manera de describir la falta de mis padres. Es la nada. Es el vacío. Es un repentino y permanente apagón de luces. Es la oscuridad. Es andar de tinieblas en la oscuridad. Es andar pedo en las tinieblas en la oscuridad. Y caerse. Y nadie te ayuda levantarte. Es no saber nadar ni poder tocar fondo. en un pinche mar profundo, sin fondo, picado y negro. Es una puta patada voladora al estómago que deja sin aliento ni posibilidades de recuperarlo. Es volver al útero, un útero terrible y frio y estéril y lleno de angustia y dolor del cual no hay salida. Es el volver a no ser, no existir. Es una chingada incertidumbre temible existencial/no existencial. Es un pinche grito infinito al infinito. No concibo. No explico. Me mudo en el silencio y en el vacío. Los que me concibieron y me trajeron a este mundo me cuidaron me dieron una crianza, paciencia, apoyo, amor. Ya no están. No los veo ni los palpo ni los puedo más sentir ni escuchar. Nunca más. No hay manera de describirlo. Ni hacer el intento. © Jaime Herrera ***Jaime H. Herrera is currently a Professor of English at Mesa Community College. Jaime is a product of the Juárez/El Paso border, a place he holds dear and which embodies who he is, as much Mexican as American, as much Mexicano (and mexinaco) as he is estadounidense (and gringo). He is bicultural and bilingual (and speaks a good Spanglish too). He knows that the border is a space that cannot be fenced. La frontera es un espacio que no se puede cercar. He loves translation, the back and forth between the two languages. Also. he writes his own poetry in both English and Spanish and has written a novel (as of yet unpublished), tentatively titled This is not Juárez. When he dies, he wants his ashes spread right in the middle of the bridge that connects Juárez and El Paso, his ashes blowing in both directions.

At Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

You know you’ve hit the border because of the wall-- two stories & grid- like holes punched into the metal so at least the wind can get through. Someone on the US side has pinned a frog--tucked each flipper into an O and left him spread-eagle & reaching. Through the O’s you see that along the Mexico side of the wall, a man drives an 80’s sedan with the window down. He waves. You wave in return. You walk along the border following the wall wondering why it is we need another wall, more barriers. You note the silence. Not even the wind utters a word. The cactus, arms raised, salute you in the distance. © Kimberly Williams This poem is dedicated to those who lost their lives in the bar in Thousand Oaks, CA. The Wait

It doesn’t take a sociopath You can wait until it comes to think like a sociopath. All your way -- at the local it takes is imagination: the synagogue, the corner Kroger, second floor outdoor balcony the campus bar mid-semester, of the college’s Business your child’s school, your neighborhood Building, the northwest church, while you sit in the pew, facing corner -- aiming toward the center the altar, the preacher, the pulpit, of campus, the students beneath the large, looming cross, with your walking to the Union to grab a bite or back to the door, sitting with your meet a friend between classes-- head exposed like a melon They don’t think, but, bone deep, they know on the vine. And you know it’s coming. © Kimberly Williams The following are three poems from my recently complete manuscript, Sometimes a Woman. The poems in this manuscript represent the lives and voices of the prostitutes and madams who were indispensable, economically and socially at the least, to settling the “Wild West.”

Roll Call of the Fancy Ladies, Yavapai County (found in Jan McKell’s Wild Women of Prescott, AZ) Part I--Mistresses of Yavapai County, 1864 Pancha Acuna, born in México, Mariana Complida, México, Theodora Dias, México, Nocolasa Frank, México, Andrea Galinda, married, born in New Mexico, Rosa Garcia, México, Perfecta Gustalo, Tucson, Santa Lopez, mistress of Negro Brown, age 17, México, Isabella Madina, México, Maria no last name, México, Laguda Martinez, Tucson, Francisca Mendez, no city given, Arizona, Juana Miranoa, México, Donanciana Perez, México, Catherine Revere, age 40, México, Acencion Rodrigues, born in México 35, Sacramenta, no last name, age 20, México. Part II -- Mistresses of Yavapai County, 1870 Census Nellie Stackhouse, born in Pennsylvania, Mollie Sheppard, born in Ireland, Maggie Taylor, age 19, born in California, Ginnie McKinnie, age 18, born in New York. Mary Anschutz, a.k.a. Jenny Schultz, no birth place listed, age 18, will be murdered in two months. Part III -- Mistresses of Yavapai County, 1880 Census Nellie Rogers, born in Illinois, lived next door to Mollie Sheppard. Elysia Garcia, age forty, lived with six unnamed ‘Mexican girls’ who ranged in age from sixteen to twenty-eight. Maria Quavaris, Pancha Bolona, and Joan Arris, all from Sonora, ages seventeen to twenty-eight, dwelled together. Living with them, Savana Deas, born in Arizona, eight months-old. End of Times: A letter to“Big Billie” Betty Wagner, Silverton, CO (found in Jan MacKell’s Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains) Dear Billie: No doubt you will be surprised to hear from me but I heard you were there and I’m writing to ask how business is and is there a chance for an old lady to come over and go to work? There is absolutely nothing here and I want to leave before the snow gets too deep. If I can get a crib or go to work in one of the joints, let me know. I wrote to Garnett and she said there wasn’t any place there I could get. Please answer and let me know. Must close now and put this in the mail. Bye-bye and answer soon. Mamie G., 200 N. 3rd St. Death Is the Only “Death is the only retirement from prostitution.” --Anonymous Prostitute, Jan McKell’s Red Light District of the Rocky Mountains Part I. Roll Call Fay Anderson, Salida, Colorado, died from carbolic acid Ettie Barker, actress, theater Comique, Pueblo, Colorado, overdosed on morphine Blanch Garland, Bon Ton Dance Hall, Cripple Creek, Colorado, died from chloroform Nellie Rolfe also overdosed on morphine, Cripple Creek Cora Davis took strychnine, Boulder, Colorado, New Year’s night 1913, and died Stella No-last-name, Boulder, Colorado, dead with no cause listed May Rikand, combined alcohol and morphine to die, Silverton, Colorado Malvina Lopez, Tombstone, double suicide with her companion, John Gibbons, by asphyxiation from burning charcoal Goldie Bauschell, Crystal Palace, Colorado City, jumped from second-story window but survived. Effie Pryor and Allie Ellis, Boulder, Colorado, double suicide by morphine. Allie survived. Nora McCord, Salida, death through unidentified pills. Nora, herself, was unidentified. She never gave her real name. Part II. Madam Maddie Silk Narrates, Boulder, CO, New Year’s Night 1913 When we nudged the door a little, it gave. Cora lay curled on her bed like she was still in utero, naked, except for the silk stockings which she prized. It took the moment, and Officer Parkhill saw a breath from her chest, and then we all held our own: she’s alive. Officer Parkhill and the other policeman lifted her off the bed and carried her down the stairs lengthwise, Mr. Parkhill lifting her shoulders and leaning her head against his chest. This is when Cora revived long enough to empty the contents of her abdomen. She turned her head and covered Office Parkhill’s chest with all the poison in the world. The officers transported Cora in the car, and I sat alongside. The 20-degrees surrounding us wanted silence, and we gave it. I had wrapped Cora in a big bear blanket, but she had settled back into the deepness of dying. Here, we delivered her to the county hospital. I’ll stay. I said. Mr. Parkhill, your suit is ruined. He agreed. The men took their hats and their way, and I settled into a night of quiet. 1913, unlucky at best. Cora died the next day. © Kimberly Williams This summer, Jaime Herrera was one of eight finalists for the 2018 Paz Prize. To celebrate this accomplishment, here are three of his prose poems from his series Cruzando la frontera.

Cruzando la frontera #30 Mi papá me consigue un carro en el deshuesadero de mi tío y me lo da para ir a la escuela y para llevar a mi hermana a la escuela y para moverme en esta ciudad ajena de El Paso. Donde vivimos en El Paso no es como mi barrio viejo con su actividad a todas horas del día; no hay el jugar con mis amigos en la tarde en la calle; no hay las noches en las cuáles las comadres salen de casa, se sientan en sus banquitos en la banqueta, y se ponen a platicar mientras yo y mis amigos y primos jugamos en la calle hasta ya entrada la noche. En mi vecindad nueva nadie nunca juega en la calle y niños no aparecen como por magia cuando boto la pelota afuera en la banqueta. Boto la pelota afuera muchas veces y intermitentemente a través de muchos días y nadie sale y estoy triste. Observo como las casas parecen vacías ya que la gente sale temprano y llega tarde y ya al entrar a sus casas la gente nunca vuelve a salir sino hasta el día siguiente a repetir el mismo patrón. Las casas como que están habitadas por fantasmas y veo a través de algunas ventanas las sombras de las personas que se mueven dentro de sus casas, pero fuera de eso no aparecen. Son casas de fantasmas. Y no conozco a nadie y no aguanto estar en El Paso y la esterilidad de donde nos mudamos. Todos los días cruzo el puente a Juárez, y regreso a mi barrio viejo a recuperar algo de mi vida vieja. Y a veces cruzo la frontera varias veces en el transcurso de un día y en la noche. Ese es mi patrón. Los fines de semana me voy al igual a Juárez y yo y mis amigos compramos caguamas Carta Blanca o litros de Brandy San Marcos y Pepsis y lo mezclamos en vasitos claros de plástico y tomamos y vagamos toda la noche, por la calle dieciséis, al centro, de un lado de la ciudad al otro. A veces ya después de medianoche paramos a comprar burritos en el Bar Tin Tan, cerca del centro. Los burritos son de tortillas de harina recién hechas por Manolo, el cocinero del bar. Manolo nos conoce y no nos deja entrar al bar ya que somos menores de edad pero nos vende burritos a través de la ventana del bar que da hacia la calle. Le da gusto vernos y nos dice que tengamos cuidado. Yo siempre manejo ya que tengo carro, pero además mis amigos dicen que ya sea esté pedo o no pedo, soy el mejor para manejar, que tengo instintos de corredor de carros. Al fin de la noche, dejo a todos en sus casas y regreso por el puente a mi casa nueva. En la mañana cuando despierto, en mi cama y en mi casa, tengo el claro sentido de haber cruzado de un mundo a otro, pero me digo que solo es el efecto del alcohol, y el efecto de la frontera. Cruzando la frontera #33 La primera vez que la hice de pollero estaba mi primo de visita de Durango con la rondalla de su prepa y me dice que él y sus amigos quieren conocer El Paso y que si los paso pero que no tienen pasaporte. Yo de mocoso de quince años les digo que sí y vamos en mi carro y en la línea les hago practicar decir “American” hasta que llegamos a la garita y el oficial nos pregunta a todos y yo y mi primo y El Chupón y La Perica y El Mariachi contestamos American pero cuando le toca a El Rino dice Amerrrican pero como con siete erres y le vuelve a preguntar el oficial y lo mismo y entonces el oficial le pregunta en ingles que qué va hacer a El Paso y Rino le contesta Amerrrican. Es cuando el oficial me dice que tenga cuidado que es un delito federal y le digo que sí señor y nos regresa por la línea opuesta y de regreso a Juárez todos nos reímos y Rino dice que se siente mal que por su culpa no pasamos y le decimos que no hay bronca. Muchos años después estoy en Durango en el mercado y se me acerca un cuate y los dos nos vemos como que nos conocemos y le digo ¿Rino? y me dice ¿Cuervo? y nos reconocemos y nos damos un abrazo y me pregunta que si me acuerdo de esa vez y dice Amerrrrican y nos echamos a reír. Cruzando la frontera #35 Un viernes por la noche me pongo una tremenda peda y al final de la noche me vomito en la banqueta enfrente de la casa de mi primo y él se baja a su casa y yo agarro camino a El Paso. Aun a las dos de la mañana hay línea en el puente y la espera me ayuda a bajarme las cervezas, pero varias veces me quedo dormido en la línea hasta que el carro detrás de mí me pita y me despierto. Estoy a medio puente y veo en la oscuridad las figuras o sombras de personas y tal vez hasta familias enteras dormidas en la banqueta justo a la mitad del puente en cajas de cartón y con cobijas y puedo divisar a niños y adultos dormidos ahí en la banqueta fría. Veo todo eso mientras se mueve la línea y es como cámara lenta y en todo ese tiempo parece que ninguno de los bultos de gente se mueve. Al llegar a la garita el de la aduana me pide mi ciudadanía y le digo American y me pregunta si traigo algo y le digo que no y pretendo que no estoy pedo y parece que se la cree ya que me dice que pase y llego a casa y entro al cuarto de mis papas y les aviso que ya llegué y me tumbo en mi cama con toda mi ropa, nomás me quito las botas. Estoy tan pedo que no recuerdo como manejé de Juárez a mi casa y cómo crucé el puente. Todo está en blanco menos una memoria vaga de una muchacha gritando a su novio déjame ya hijo de puta ya no te quiero y él la persigue por entre los carros y ella me toca en el vidrio y me dice que es un hijo de puta y le digo que todos lo son y él la alcanza, pero llegan unos policías y se los llevan a los dos. Y recuerdo además unas figuras muertas en la oscuridad. Me duermo. Y no es la única ni la última vez que vuelvo a hacer lo mismo. Cuando despierto en la mañana lo primero que hago es ver si está mi carro afuera y sí está, aunque no sé cómo llegué y de pronto no sé dónde estoy. Pero está mi carro y estoy yo y me vuelvo a dormir. Y no es la única ni la última vez que vuelvo a hacer lo mismo. Le cuento a Gabriel y me dice que soy un borracho y nos reimos. Muchos años después me dice un psicólogo: no es que eras un borracho, aunque tal vez lo eras. Más bien es el efecto de estar desplazado, de un sentido profundo de pérdida. Y cuando me dice eso, me pongo a llorar. © Jaime Herrera Cruzando la frontera #27

Por Jaime Herrera Un sábado batí mi record de cruzar el puente: cinco veces (viajes redondos en la camioneta que me presta mamá). 1. En la mañana crucé temprano a El Paso a jugar basket y regresé a casa a comer. 2. Después de comer fui a la escuela en El Paso para hacer limpieza y regresé a casa, a bañarme; 3. En la tarde fui a El Paso a salir con mi novia. Fuimos al cine. Sus papás no la dejan ir a Juárez y me despedí de ella en tiempo para ir a cenar a casa. 4. Ya de noche salí con mis amigos y decidimos ir a El Paso a pistear. Me regresé a pie a Juárez porque perdí las llaves de la camioneta; 5. Regresé a pie a El Paso con las llaves de repuesto y justo antes de medianoche regresé a Juárez con mis amigos para seguir la peda en Juárez. En la mañana, en mi cama en mi casa, despierto con un sentido de haber cruzado muchos mundos muchas veces, pero me digo que solo es la cruda y el efecto de la frontera. Cruzando la frontera #28 Después de años de decir que nos íbamos a vivir a El Paso, un viernes ya tarde llega papá en sus copas. Nos dice que mañana mismo nos vamos a El Paso y para mi sorpresa el sábado por la mañana llegan mis tíos con sus trocas y vamos al puente Córdova con todas nuestras pertenencias (otra vez) y pasamos por aduana y cruzamos el puente y nos mudamos a El Paso y aunque la distancia no es mucha, tal vez menos de diez kilómetros, para mí es como ir al otro lado del mundo. Tengo catorce años y me siento desterrado y es cuando comienzo a beber. © Jaime Herrera |

Kimberly WilliamsKimberly has been fortunate to travel to half the Spanish-speaking countries in the world by the time she was forty. As a traveler into different cultures, she has learned to listen ask questions, and seek points of connections. This page is meant to offer different points of connections between writers, words, ideas, languages, and imaginations. Thank you for visiting. Archives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed